By Umair Jamal

The June 25 meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Defence Ministers in China illuminated how enduring tensions between Pakistan and India are hindering the bloc’s counterterrorism initiatives while compounding New Delhi’s diplomatic challenges within the organization. India’s refusal to endorse the meeting’s joint communiqué, following its unsuccessful attempt to include references to the April 2025 Pahalgam attack in Indian-administered Kashmir, demonstrated its waning influence in Eurasian multilateralism. Whereas Pakistan succeeded in presenting the unrest in Baluchistan as a matter of SCO concern, India was unable to garner support for its narrative on Kashmir. Concurrently, China’s advocacy for a more pronounced Iranian role in the SCO—evident in the forum’s condemnation of Israeli military actions, which India opposed—suggests a growing divide, potentially transforming the organization into a venue for great-power rivalry. This impasse accentuates India’s strategic dilemma: it must either align with the SCO’s emerging anti-Western consensus or risk marginalization within the China-dominated security framework of Central Asia.

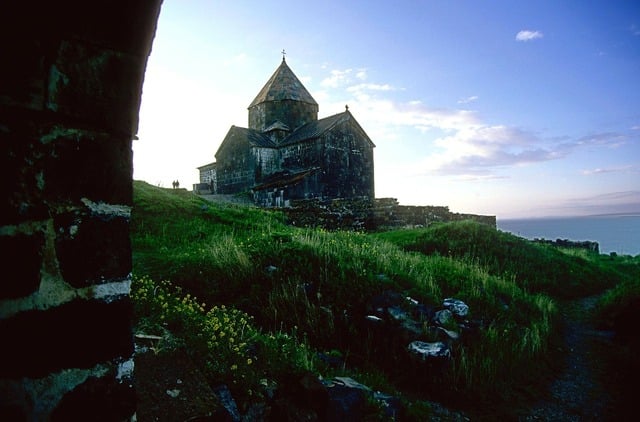

The 2022 Meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Council in Samarqand, Uzbekistan. Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

BACKGROUND: The SCO evolved from the 1996 Shanghai Five, initially established as a Sino-Russian initiative aimed at stabilizing Central Asia. However, its enlargement in 2017 to include both Pakistan and India introduced volatile bilateral dynamics into the organization. Traditionally, the SCO has concentrated on combating the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism, yet the divergent stances of India and Pakistan have increasingly politicized these very concerns. Pakistan characterizes India’s actions in Kashmir as constituting state terrorism. Islamabad maintains its support for the region’s right to self-determination and remains committed to a negotiated resolution of the dispute. In contrast, India accuses Pakistan of facilitating cross-border militancy, resulting in an impasse that has repeatedly obstructed consensus within the SCO.

The April 2025 attack in Pahalgam, which resulted in the deaths of 26 tourists, along with India’s subsequent missile strikes on Pakistan, significantly escalated bilateral tensions in the weeks leading up to the SCO meeting in China. India’s effort to raise the Kashmir issue during the SCO Defence Ministers’ meeting proved unsuccessful, as references to the matter were excluded from the preliminary joint communiqué intended for endorsement by all member states. In contrast, Pakistan’s inclusion of references to unrest in Baluchistan in the draft appeared to align more closely with the organization’s stance against external interference, thereby garnering broader resonance within the bloc.

China’s discreet yet consistent support for Pakistan has altered the internal dynamics of the SCO in recent years. On multiple occasions, Beijing has permitted Islamabad to obstruct India’s terrorism-related narratives, while simultaneously advancing its own conception of the SCO as a counterweight to the U.S.-led international order. For example, India’s recent refusal to endorse the SCO’s condemnation of Israel’s attack on Iran further isolated New Delhi from the prevailing consensus within the group, highlighting its increasing divergence from the bloc’s anti-Western trajectory. This discord is structural in nature. India’s strategic alignments with the U.S. through frameworks such as the QUAD and I2U2 are at odds with the SCO’s objectives, whereas Pakistan’s China-backed diplomatic strategy aims to leverage the organization to constrain India’s influence. With Iran’s accession as a full member, the SCO is likely to intensify its anti-Israel and anti-American rhetoric, thereby compelling India to confront progressively more difficult diplomatic trade-offs.

IMPLICATIONS: The persistent tensions between India and Pakistan during SCO meetings are generating substantial obstacles for the organization while reshaping regional power dynamics. India increasingly finds itself in a strategic quandary. Remaining within the SCO necessitates engagement with both Pakistan and China on contentious issues such as Baluchistan and may compel tacit support for initiatives aligned with Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Conversely, a complete withdrawal from the forum would entail forfeiting strategic influence in Central Asia, thereby ceding greater regional influence to China and Russia.

Recent military confrontations between India and Pakistan underscore how their bilateral disputes are impeding the SCO’s capacity to foster effective security cooperation. Although the U.S. facilitated a ceasefire between the two countries following the latest clashes, the underlying issue persists: India aspires to leadership within the Global South, yet its strategic vision diverges from the SCO’s predominantly anti-Western orientation. India’s choice not to utilize the SCO platform to present its case against Pakistan after the Pahalgam attack reflects a diminishing confidence in the organization. Despite actively engaging Western capitals to highlight the issue of cross-border terrorism in the aftermath of its retaliatory strikes, India conspicuously refrained from advancing its position during the SCO summit.

This pattern of selective engagement suggests that New Delhi perceives the China-led forum as increasingly peripheral to its core security interests—a perception that stands in sharp contrast to its intensified diplomatic outreach to the U.S. and EU in recent weeks. India’s disengagement from the forum conveys a clear signal to states such as Pakistan and China: New Delhi prioritizes its Western alliances over participation in Eurasian multilateral mechanisms. By choosing not to raise the Pahalgam incident within the SCO framework, India implicitly acknowledged the organization’s limited utility in addressing its counterterrorism agenda. However, this strategy entails certain risks, as India’s terrorism-centric narrative, promoted primarily through its Western partnerships, has recently received limited international traction. Many states remain preoccupied with the potential nuclear implications of India-Pakistan tensions, while terrorism-related issues have garnered comparatively little global attention.

India’s marginalization within the SCO may inadvertently enhance Pakistan’s standing as the more engaged and consistent Eurasian partner, thereby exposing the limitations of New Delhi’s multi-alignment strategy. Pakistan has strategically leveraged the SCO platform to elevate its international profile, presenting itself as a cooperative actor aligned with the organization’s principles.

Meanwhile, Islamabad actively seeks to obstruct Indian statements that conflict with its strategic interests, while simultaneously reinforcing its alliance with Beijing. By focusing on shared security concerns—such as terrorism—that resonate with Central Asian member states, Pakistan positions itself as a more constructive and cooperative actor within the SCO framework. In contrast, India’s persistent emphasis on Pakistan’s alleged support for terrorism in Kashmir is perceived by other members as invoking a protracted bilateral conflict that necessitates substantive dialogue between the two parties. Within this context, the SCO is viewed as a potential facilitator, but only if both countries demonstrate a willingness to engage. While Pakistan has signaled openness to such mediation through the SCO, India has consistently rejected third-party involvement in the Kashmir dispute.

China appears to be the primary beneficiary of the ongoing India-Pakistan rivalry within the SCO. It leverages these divisions to diminish India’s influence in Eurasian institutions, to assess the reliability of Russia—traditionally a neutral actor—and to advance its own financial mechanisms as alternatives to Western systems. In this context, Iran’s accession as a full member introduces additional complexities for India, compelling it to navigate between aligning with SCO positions and preserving its expanding strategic relations with Israel. Moreover, Iran’s inclusion is likely to enhance coordination between China and Pakistan on issues such as Afghanistan and regional energy initiatives, thereby increasing the risk of India’s marginalization within the organization.

India’s challenges within the SCO undermine its credibility as a self-proclaimed leader of the Global South. Its positions frequently diverge from those of the majority of member states, thereby casting doubt on its representative claims. The SCO’s counterterrorism cooperation has also been significantly impeded by the India-Pakistan impasse, which prevents joint military exercises, intelligence sharing, and meaningful dialogue on bilateral tensions. This persistent dysfunction has historically provided greater operational latitude for militant groups and carries the risk of escalating into open conflict, as illustrated by the aftermath of the Pahalgam attack.

CONCLUSIONS: The SCO has arrived at a critical juncture, as the enduring rivalry between India and Pakistan continues to obstruct its operational efficacy. India’s marginalization at recent meetings underscores its difficulty in reconciling strategic partnerships with the U.S. and effective engagement within a China-led multilateral framework. Meanwhile, Pakistan—bolstered by Chinese support—has adeptly utilized the SCO as a platform to contest India’s stance on Kashmir and to portray itself as a constructive and responsible partner in counterterrorism efforts.

Looking ahead, three scenarios appear increasingly plausible. First, the existing stalemate may persist, with India continuing to obstruct references to Kashmir and Baluchistan while opposing proposals perceived as anti-Western. Second, Iran’s recent accession to the forum may consolidate an anti-U.S. and anti-Israel bloc within the SCO, further marginalizing India’s influence. Third, China may exploit these internal divisions to transform the SCO into a vehicle for advancing its Belt and Road Initiative, thereby diminishing India’s strategic role within the organization.

For the SCO to retain its relevance, it would need to play a constructive role in resolving disputes between India and Pakistan; however, China’s evident alignment with Pakistan renders this prospect improbable. The organization’s viability as a significant security platform now hinges on its capacity to transcend its current status as merely another stage for persistent India-Pakistan rivalry. With each successive meeting concluding without consensus, the prospects for such a transformation appear increasingly uncertain.

AUTHOR'S BIO: Umair Jamal is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Otago, New Zealand, and an analyst at Diplomat Risk Intelligence (DRI). His research focuses on counterterrorism and security issues in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the broader Asia region. He offers analytical consulting to various think tanks and institutional clients in Pakistan and around the world. He has published for several media outlets, including Al-Jazeera, Foreign Policy, SCMP, The Diplomat, and the Huffington Post.

By Sergey Sukhankin

Kazakhstan has finalized its decision regarding the bidder selected to construct its inaugural nuclear power plant (NPP). Contrary to earlier projections favoring a Chinese provider, the Russian state corporation Rosatom has assumed the leading role within the international consortium. However, this outcome is unlikely to marginalize Chinese interests: a Chinese firm is expected to lead the construction of a subsequent NPP, while Chinese companies are concurrently gaining prominence in other vital sectors of Kazakhstan’s (and Central Asia’s) economy, including renewable energy and water management. Western firms appear to be the principal losers, as their capacity to expand into the most lucrative and strategic segments of Kazakhstan’s economy is likely to diminish.

The Beloyarsk Nuclear Power Plant in Russia. Image Courtesy of IAEA Imagebank

BACKGROUND: In October 2024, following a national referendum in which over 71 percent of voters supported the construction of a nuclear power plant (NPP) in Kazakhstan, local authorities prouced a shortlist of prospective bidders. This included China’s CNNC, Russia’s Rosatom, South Korea’s KHNP, and France’s EDF. The selection process extended beyond economic rationale and was clearly shaped by geopolitical considerations: although Kazakhstani authorities initially intended to make a decision by the end of 2022, the deadline was repeatedly postponed. Despite widespread confidence among local experts that CNNC would prevail, and notable public support for the French and South Korean contenders, on June 14 it was officially announced that Russia’s Rosatom would lead the international consortium responsible for building the NPP.

However, appointing Rosatom to oversee Kazakhstan’s first NPP does not signify exclusive Russian dominance in the country’s emerging nuclear sector. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev had previously stated that, to avert a foreseeable energy shortage, Kazakhstan would require not one but three NPPs. Furthermore, Minister of Energy Almasadam Sätqaliev publicly indicated that CNNC would likely head the consortium for the construction of another NPP. Tokayev later reaffirmed this during a meeting with Xi Jinping, assuring the Chinese leader that, given Kazakhstan’s need for 2–3 NPPs, CNNC is regarded as a reliable strategic partner with a secured role in the domestic market.

IMPLICATIONS: In many respects, Kazakhstan’s decision to appoint Rosatom as the head of the international consortium is readily explicable and can be attributed to two principal factors. First is the logic of “do-not-poke-the-bear” thinking. A combination of adverse developments and humiliations—the stalled “three-day war” in Ukraine, increasing economic and political isolation, and a series of setbacks in the Middle East—has rendered the Russian political elite particularly sensitive to any potential rejection of its bid by Kazakhstan. Furthermore, Kazakhstan has once again declined to join BRICS, a move that visibly displeased Moscow. At this juncture, it is worth recalling that on May 29, Vladimir Putin met with Kazakhstan’s first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev—an event that, according to some experts, may be interpreted as part of Russia’s exertion of political pressure on Kazakhstan’s current leadership in relation to the NPP project.

Despite Russia’s ongoing decline, Kazakhstan’s accommodation of Russia’s NPP-related interests is not unexpected: when cornered, the Russian regime is capable of undertaking retaliatory measures—such as provocations, subversion, or other forms of pressure—against the significantly smaller Kazakhstan. Conversely, experts have acknowledged that the selection of Rosatom may also possess an element of rationality. Analysts based in Kazakhstan emphasize Russia’s notable competitive advantages, which include cultural and linguistic proximity as well as logistical and technological compatibility. Moreover, Uzbekistan’s decision to finalize an agreement for the construction of a small NPP—an agreement that has since been upgraded in scope—may have further influenced Kazakhstan’s preference for Rosatom. Importantly, Rosatom is not subject to international sanctions, and the likelihood of its inclusion on such lists does not appear imminent.

That said, uncertainty remains regarding how Kazakhstan would respond should the corporation become subject to Western sanctions or if Russia’s macroeconomic conditions deteriorate further. Although Russia reportedly offers Kazakhstan favorable credit terms—details of which remain undisclosed—Kazakhstan-based experts highlight that Russia has previously failed to fulfill its commitments to finance energy infrastructure projects in three Kazakhstani cities. Moreover, citing the Belarusian case, anonymous Russian sources caution that partnering with Rosatom may ultimately impose a financial burden on Kazakhstan, despite the apparent economic appeal of the offer, and could also give rise to significant safety concerns over time.

Russia, however, will not be the sole dominant actor in Kazakhstan’s emerging nuclear energy sector. As previously noted, the local ruling elite regards China as a crucial component of the equation and, seemingly, as a counterbalancing force to Russia. For its part, Beijing will capitalize on several competitive advantages as it seeks to expand its influence within the country and its nuclear industry.

First, China is intensifying its cooperation with Kazakhstan in the field of water management, a domain of critical importance given the deteriorating conditions in the Caspian Sea. For example, during a recent meeting between Chinese and Kazakh water management experts, it was agreed that China Energy International Group would provide comprehensive training and expertise to its Kazakh counterparts. Additionally, it was disclosed at the meeting that the company is actively exploring the construction of a hydroelectric power facility in Kazakhstan and has expressed interest in participating in projects focused on the digitalization and automation of the country’s water management sector. Beyond current challenges with water supply, Kazakhstan’s ambitious plans to develop green hydrogen—which demands significant water resources—underscore water management as a strategic priority, and China is poised to expand its involvement in this area.

Second, China is rapidly enhancing its role in one of Kazakhstan’s most promising economic sectors—its uranium industry. Kazakhstan ranks first globally in uranium production and holds the second-largest uranium reserves after Australia, where production may decline due to growing public opposition. In light of ongoing geopolitical instability in Sub-Saharan Africa, Kazakhstan and Canada are likely to remain the two leading uranium producers, maintaining dominance in the global market. In this context, China could support Kazakhstan in addressing two major constraints limiting the full exploitation of its uranium resources: the absence of domestic enrichment capabilities and the continued reliance on Russia for uranium export logistics.

It is thus worth noting that Rosatom-affiliated Uranium One Group recently concluded an agreement with the Chinese firm SNURDC Astana Mining Company Limited, a subsidiary of the State Nuclear Uranium Resources Development Co., Ltd. Under this arrangement, the Russian party transferred its shares in uranium production sites located in Northern Kazakhstan (Northern Khorasan) to its Chinese counterpart. Although experts remain divided on China’s rationale for acquiring stakes in what is viewed as a relatively depleted and marginal uranium site, many interpret this as a strategic move to further expand China’s presence in Kazakhstan. In any case, an increasing foothold in the country’s uranium sector could serve as a compelling argument in China’s favor in its pursuit of the NPP project.

Finally, Kazakhstan must recognize the potential consequences it may face in the near future if it fails to deepen its cooperation with China in nuclear and other forms of clean energy. Many experts contend that China’s rapid shift toward renewable energy signals a troubling trend for its hydrocarbon suppliers, including Kazakhstan. At present, renewable sources account for 80 percent of China’s energy and electricity demand, while fossil fuels still constitute approximately 62 percent of its overall energy consumption. However, the proportion of non-renewable energy in China’s energy mix is expected to decline further. This trajectory suggests that Kazakhstan should proactively explore alternative areas of economic cooperation—such as critical metals, renewable energy, and nuclear power—with its principal economic partner, especially in light of Beijing’s strategic direction and the intensifying competition from regional actors like Uzbekistan, where China is also expanding its presence.

CONCLUSIONS: Kazakhstan’s decision to appoint Rosatom de facto as the lead entity in constructing its first nuclear power plant (NPP) reflects a blend of economic, geopolitical, and symbolic considerations. The second NPP will most likely be built by China, which is simultaneously consolidating its position in Kazakhstan’s water management and renewable energy sectors—domains poised to drive economic growth across Central Asia for decades to come. For Russia, weakened and humiliated in Ukraine and the Middle East, the opportunity to construct Kazakhstan’s inaugural NPP represents a highly symbolic gesture, acknowledging its ongoing role in bilateral relations. Kazakhstan’s choice to prioritize a Sino-Russian consortium—though the long-term stability of this partnership remains uncertain—for shaping the country’s nuclear future effectively establishes a duopoly in this sector of the national economy. This development may be unwelcome news for Western actors, whose companies are unlikely to secure significant contracts in Kazakhstan’s most strategic economic sectors.

AUTHOR'S BIO: Dr. Sergey Sukhankin is a Senior Fellow at the Jamestown Foundation and the Saratoga Foundation (both Washington DC) and a Fellow at the North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (Canada). He teaches international business at MacEwan School of Business (Edmonton, Canada). Currently he is a postdoctoral fellow at the Canadian Maritime Security Network (CMSN).

By Suren Sargsyan

Donald Trump’s return to the White House marked significant shifts in U.S. foreign policy. His second presidential term not only departs from the foreign policy approach of the Biden administration but also diverges considerably from his own first term. The rapidly evolving trajectory of U.S. foreign policy has profound implications—not only for U.S. allies but also for countries and regions that are directly or indirectly affected by changes in Washington's global posture. The status of the South Caucasus, which has seen varying degrees of U.S. engagement and interest over the years, has become increasingly unclear in the Trump administration’s foreign policy, despite pivotal geopolitical developments that increase the region’s significance.

BACKGROUND: Scholarly literature reflects a range of views regarding Western, and particularly U.S. interests in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. One prevailing argument suggests that the West has historically exhibited limited engagement in these regions, largely because they have been traditionally considered part of Russia’s sphere of influence. Some analysts even contend that, with the exception of the Baltic states, most former Soviet republics have been implicitly regarded as falling within Russia’s zone of control by Western powers themselves.

Conversely, a competing viewpoint asserts that the U.S. has maintained clear, albeit non-vital, strategic interests in the region. While not central to U.S. foreign policy, these interests are nonetheless significant. Accordingly, Washington has sought to exert influence when opportunities have presented themselves most notably in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse, following the September 11 terrorist attacks, and after the 2008 Russo-Georgian war.

At various times and for varied reasons, U.S. policy toward the countries of Central Asia has gained increased attention, often surpassing the level of engagement shown toward the South Caucasus. This heightened focus has been driven by several key factors. Notably, following the events of September 11, 2001, Central Asia became strategically important for the conduct of U.S. military operations in Afghanistan. In addition, the region has been viewed as a critical arena for geopolitical competition with Russia and China. The presence of significant energy resources has further elevated the strategic value of Central Asia in U.S. foreign policy calculations.

It is also important to recognize that the U.S. has rarely articulated official, standalone strategies for individual regions such as the South Caucasus. Exceptions exist—for instance, the Trump administration’s publication of a formal strategy for Afghanistan in 2017 or Central Asia Strategy of 2019 but they are rare. Often, regions like the South Caucasus are subsumed under broader strategic frameworks, such as the Caspian Basin, Eurasia, or the Greater Middle East. Within this context, U.S. policy toward Iran also influenced engagement with the South Caucasus. Even in the absence of a declared strategy, U.S. efforts to isolate Iran often relied on close cooperation with neighboring states, including Armenia and Azerbaijan. Similarly, the U.S. viewed Georgia—and, to a lesser extent, Armenia—as potential counterweights to expanding Russian influence in the region. Moreover, Washington saw the normalization of Armenian-Turkish and Armenian-Azerbaijani relations and the opening of their shared border as strategically important. Only under such circumstances could the closure or limiting the capabilities of the Armenia-Iran border be considered a feasible long-term policy goal. Since the early 1990s, the U.S. has sought to play an active role in addressing regional conflicts and unresolved issues, recognizing that the persistence of such disputes could create opportunities for the resurgence of Russian influence in the region. This understanding also underpinned Washington's active involvement in the OSCE Minsk Group and its support for the negotiation process regarding the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

IMPLICATIONS: During Donald Trump’s first presidency, U.S. policy toward the South Caucasus was relatively passive. Throughout those four years, there were very few direct and active engagements with the leaders of South Caucasus countries, reflecting a lack of a robust or comprehensive bilateral agenda. While cooperation has taken place in specific areas, the U.S. did not maintain an active, coordinated, or consistent presence in the region. This changed significantly under President Joe Biden, particularly after the 2020 war between Armenia and Azerbaijan and even more so following the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine beginning in 2022. Biden moved quickly to become involved in the South Caucasus, positioning the U.S. as a mediator in both Armenian-Azerbaijani and Armenian-Turkish relations. Under leadership of President Biden and Secretary of State Blinken, Armenian-Azerbaijani and Armenian-Turkish negotiations gained momentum. There was a concerted effort to reach a peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan during Biden’s presidency, especially since the bulk of the negotiations had taken place under the mediation of his administration. However, the Democratic Party’s electoral defeat created a complicated situation. The new Trump administration appears to place little priority on the fact that the peace agreement is essentially ready, with only a few unresolved points remaining before it can be signed. As for the Armenian-Turkish negotiations, they too seem to have stalled under the current administration, suggesting a broader slowdown in U.S. engagement in the region's peace processes.

Moreover, several pressing questions remain unanswered. It is unclear how the U.S. envisions its mediating role within the framework of an Armenian-Azerbaijani peace agreement. Equally ambiguous is the meaning behind Trump advisor Steve Witkoff’s recent comment suggesting that Armenia and Azerbaijan could join the Abraham Accords. There is also uncertainty about the future of U.S. policy toward Georgia—once considered a strategic partner but now appearing to have lost that status—as well as toward Armenia, which was granted a similar strategic designation just days before President Biden's departure. More broadly, it remains unclear whether the U.S. views the South Caucasus as a cohesive regional unit or continues to approach it as a collection of separate, unrelated states.

CONCLUSIONS: Maintaining a presence in the South Caucasus requires effective engagement with each state individually. However, a regional approach remains essential. Within Trump’s team, there appears to be a growing understanding of the significance of the South Caucasus for Russia, Iran, and Turkey not only geopolitically but in broader historical context. As a result, extending U.S. influence in the region would require both a clearly defined regional strategy and tailored bilateral tools, including the application of soft power. Yet the Trump administration’s limited interest in soft power (cutting all foreign assistance programs), its lack of enthusiasm for deepening bilateral partnerships, and its relatively passive role in regional conflict resolution, all point towards the absence of a strategic approach toward the South Caucasus. The Trump administration still lacks a concrete policy toward the South Caucasus as a region, as well as clear strategies for conflict resolution in the region and distinct approaches to Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan individually.

This will complicate the efforts of future U.S. administrations to establish meaningful involvement in the region and could create an environment conducive to the emergence of regional formats like the 3+3 platform (involving Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Russia, Turkey, and Iran). The establishment of such a framework would effectively push not only the U.S. but also the EU out of the region—at a time when the EU is struggling to maintain relevance in global geopolitics, especially as long as Washington acts unilaterally. A withdrawal of U.S. influence from the South Caucasus would make reengagement either impossible or extremely difficult. Therefore, if the U.S. aims to maintain influence in a region bordered by its historical rival Iran, strategic competitor Russia, and a problematic ally in Turkey, Washington must, at the very least, preserve its current level of influence. This includes deepening strategic relationships, applying soft powr, and fostering new economic and business ties. Within this context, it would be logical for the administration to intensify its efforts to support the normalization of relations between Armenia and Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan, as well as enhance its engagement with Georgia. Unresolved issues in the region will prevent the U.S. from achieving a robust strategic presence—not only across the South Caucasus as a region but also within the individual countries that comprise it.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Suren Sargsyan is a PhD candidate in U.S. foreign policy towards the South Caucasus. He holds LLM degrees from Yerevan State, the American University of Armenia, and Tufts University. He is the director of the Armenian Center for American Studies.

By Nargiza Umarova

The fourth session of the India–Central Asia Dialogue at the level of foreign ministers convened in New Delhi on 6 June 2025. The concluding communiqué underscored the significance of Iran’s Chabahar Port in advancing trade connectivity between the Central Asian republics and India, and beyond.

The Indo-Iranian Chabahar initiative competes with the port of Gwadar, a pivotal component of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which envisages the integration of Central Asia through the development of a trans-Afghan railway. Concurrently, Russia is pursuing its distinct agenda by engaging with the Taliban to extend the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) into Afghanistan. Under such conditions, the Central Asian republics face the risk of becoming entangled in a cycle of great power competition, thereby endangering their own national interests.

BACKGROUND: Since 2020, Uzbekistan has engaged in dialogue with India and Iran regarding the joint utilization of the deep-water port of Chabahar, which provides direct access to the Indian Ocean. Situated in southeastern Iran, the port constitutes a critical component of Tashkent’s strategy to develop southern transit corridors and diversify freight transportation routes. Chabahar functions as a commercial gateway to Central Asia and Afghanistan, affording major global economies—especially India—access to key regional resources. This underlies New Delhi’s commitment to upgrading the Shahid Beheshti terminal in Chabahar and enhancing the surrounding transport infrastructure.

Moreover, transit through Iran reduces the cost and duration of Indian cargo shipments to and from Central Asia by nearly one-third relative to maritime routes via Europe or China. India’s objective extends beyond securing efficient and affordable access to uranium, oil, coal, and other raw materials from Central Asia; it also involves circumventing its principal rival, Pakistan.

The Indian transit corridor to Central Asia, originating at Chabahar, may proceed through both Iran and Afghanistan. In 2020, Iran commenced construction of the 628-kilometer Chabahar–Zahedan railway line, with financial assistance from India. Work on this segment is nearing completion. The route is projected to continue toward the Turkmenistan border, traversing the northern Iranian cities of Mashhad and Serakhs. En route, the Chabahar–Zahedan–Mashhad railway will diverge toward the city of Khaf, where the inaugural cross-border rail link between Iran and Afghanistan begins.

The construction of the 225-kilometer railway linking Khaf to Herat in Afghanistan is also approaching completion. Its designed capacity is estimated at up to three million tons annually, with transit cargo expected to comprise more than half of this volume. Consequently, the Khaf–Herat railway is poised to be integrated into a broader China-led transport initiative connecting East and West through Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Iran. Owing to its direct linkage with Afghanistan, Uzbekistan stands to benefit from this configuration by enhancing its own transit capacity. The Taliban administration seeks comparable advantages for Afghanistan and is actively encouraging Tashkent to extend the railway from Mazar-i-Sharif to Herat. While such an extension would grant Uzbekistan additional access to Chabahar by circumventing Turkmenistan, it could also redirect China–Europe–China transit cargo toward other neighboring states bordering Afghanistan.

IMPLICATIONS: For several years, Iran has actively pursued the realization of the China–Kyrgyzstan–Tajikistan–Afghanistan–Iran railway corridor, commonly referred to as the “Five Nation Road.” The Afghan segment of this 2,100-kilometre overland route will primarily comprise the railway currently under construction between Mazar-i-Sharif and Herat. From Mazar-i-Sharif, the transportation network would require only an extension to Sherkhan Bandar in Kunduz Province to establish a connection with the Tajik border. This development would facilitate Tajikistan’s access to Iran through Afghan territory, thereby definitely weakening Uzbekistan’s competitive position in regional transit logistics.

The Taliban regard the Mazar-i-Sharif–Herat railway as an integral element of a broader initiative aimed at establishing a Trans-Afghan corridor extending through Kandahar to Pakistan, analogous to Uzbekistan’s proposed Kabul Corridor. In 2023, the Afghan authorities announced plans to construct the Mazar-i-Sharif–Herat–Kandahar railway, which, according to media sources, is projected to provide the shortest overland route between Moscow and New Delhi via Afghanistan. Russia, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and even Turkey have been invited to invest in the venture.

The attractiveness of the Kandahar Corridor lies in its capacity to extend toward both Iran and Pakistan. Ashgabat and Astana are already advancing a new transit route from the Torghundi railway station, located at the Afghan–Turkmen border, toward Pakistan, traversing western Afghanistan. Recently, the Russian Ministry of Transport announced the initiation of a feasibility study for the Trans-Afghan railway, covering the Mazar-i-Sharif–Herat–Kandahar–Chaman route.

Without reaching Kandahar in the city of Delaram, both lines could be redirected westward and linked to Iran’s Zahedan via Zaranj in Nimroz Province, ultimately reaching the port of Chabahar.

Consequently, the Central Asian states will gain an additional opportunity to access the warm waters of the Indian Ocean. However, this scenario presents significant implications for Uzbekistan. Foremost, the advancement of the Kandahar Corridor—regardless of whether it extends toward Iran—raises concerns regarding the viability of the Trans-Afghan Railway via Kabul, which Tashkent has identified as a core interest. The simultaneous operation of both routes will inevitably result in competition for transit cargo, thereby impacting their overall profitability. Uzbekistan is will unlikely be able to impede the construction of the Mazar-i-Sharif–Herat railway, as the initiative partially aligns with the interests of Russia, India, Iran, and China. Under such circumstances, preserving the relevance of the Kabul Corridor—particularly amid funding constraints—becomes exceedingly challenging.

Secondly, the construction of the Zaranj–Delaram railway line will establish conditions conducive to the redistribution of cargo flows transiting Afghanistan toward South Asia and beyond, in favor of Chabahar. This development represents a direct challenge to the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, the most costly and prominent flagship project of the Belt and Road Initiative, which prioritizes the expansion of the Gwadar port on Pakistan’s Arabian Sea coast. Enhancing Chabahar’s transit capacity through the creation of a comprehensive network of rail and roads linking the port to neighboring countries and regions within Iran’s periphery may diminish the significance of the Kabul Corridor as a land bridge between the poles of continental Asia.

Should the Kandahar route be developed and extended into Iran, Gwadar will be compelled to share prospective cargo flows with Chabahar, thereby intensifying the rivalry between New Delhi and Beijing. Russia must also be considered, as it views the Trans-Afghan Railway as a means to extend its flagship International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) into Afghanistan. Preliminary estimates place the volume of Russian cargo on the Trans-Afghan route at between 8 and 15 million tons annually. In light of escalating tensions between Kabul and Islamabad, as well as the generally unstable security climate in Pakistan—particularly in the provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, through which two proposed railway branches from Central Asia to Indian Ocean ports are planned—Russia may opt to reroute a portion of its exports to Chabahar via Afghanistan. Over time, this shift could also influence freight transit patterns from Northern Europe to India.

Nevertheless, the ongoing escalation of armed conflict between Iran and Israel introduces significant uncertainty regarding the feasibility of such transport configurations. A protracted period of hostilities, accompanied by potential political destabilization within Iran, will unavoidably impact the reliability of established logistics networks in West Asia, potentially necessitating their complete reconfiguration. Under these conditions, both the trans-Afghan corridors leading to Iran and the Indian access route to Central Asia via Afghanistan will be placed at considerable risk. This situation will undoubtedly compel stakeholders to revise their strategies concerning the Chabahar project and to place greater emphasis on leveraging Pakistan’s transit capabilities.

CONCLUSIONS: Uzbekistan’s proactive engagement in the development of a network of trans-Afghan trade routes is anticipated to yield both economic and political advantages by enhancing its national and regional transit capacity. However, realizing these outcomes will require Tashkent to navigate carefully among the interests of global and regional powers, whose influence may significantly shape the implementation of specific transport initiatives within Afghanistan.

For the Central Asian states, maintaining diversified access to the southern ports of Iran and Pakistan is advantageous, provided that intra-regional competition is avoided, as such rivalry could undermine their collective competitiveness along the trans-Afghan corridor. Accordingly, it is essential to implement a coordinated policy aimed at identifying and advancing mutually beneficial transport routes through Afghanistan. Reaching consensus on a unified negotiating stance in engagements with the Afghan leadership is vital to mitigate the risk of the Taliban enacting externally influenced political decisions that may contradict the interests of Central Asian states.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Nargiza Umarova is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Advanced International Studies (IAIS), University of World Economy and Diplomacy (UWED) and an analyst at the Non-governmental Research Institution “Knowledge Caravan”, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Her research activities focus on developments in Central Asia, trends in regional integration and the influence of great powers on this process. She also explores Uzbekistan’s current policy on the creation and development of international transport corridors. She can be contacted at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .

Feature Articles

|

Earlier Articles

|

The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst is a biweekly publication of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program, a Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center affiliated with the American Foreign Policy Council, Washington DC., and the Institute for Security and Development Policy, Stockholm. For 15 years, the Analyst has brought cutting edge analysis of the region geared toward a practitioner audience.

Sign up for upcoming events, latest news, and articles from the CACI Analyst.