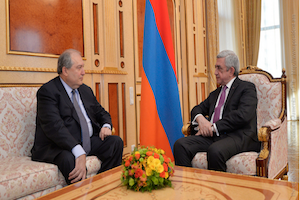

Armenia Elects New President

By Natalia Konarzewska

April 2, 2018, the CACI Analyst

On March 2, Armenia’s National Assembly elected Armen Sargsyan as president. This was the first presidential election in Armenia after the constitutional amendments adopted in 2015, which envisage a shift from a semi-presidential to a parliamentary system of government. The new system limits the president’s role to a ceremonial figure, while allocating more executive power to the prime minister who will be nominated in April when incumbent President Serzh Sargsyan’s (not related) term ends. The new president’s strong foreign policy credentials will expectedly advance Armenia’s interests abroad, which is especially important as the country hopes to rekindle relations with Euro-Atlantic structures.

Kyrgyzstan's Election Controversy: Cause for Concern?

By Jacob Zenn

November 9, 2017, the CACI Analyst

On October 16, Kyrgyzstan announced that the winner of the country’s presidential election with 54 percent of the vote was Sooronbay Jeenbekov. The election nonetheless received criticism for the way it was carried out from international organizations such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Other commentators have noted that the departing president, Almazbek Atambayev, also invested personal and state resources to support Jeenbekov’s election. Kyrgyzstan’s reputation as the “island of democracy” in Central Asia has suffered a setback. Amid other concerns about jihadist radicalization in the country, Kyrgyzstan will struggle to reclaim its reputation as a democratic model for the region, especially in the eyes of its neighbors.

Party Restructuring in Kyrgyzstan Prior to 2015 Elections

By Arslan Sabyrbekov (05/27/2015 issue of the CACI Analyst)

Kyrgyzstan’s political parties are aligning for the upcoming parliamentary elections. On May 21, the two political parties Butun Kyrgyzstan (United Kyrgyzstan) and Emgek (Labor) officially announced their unification, despite differences in political program and ideology. During their joint press conference, the leaders of the newly created party “Butun Kyrgyzstan Emgek” stated that they have agreed on all the essential positions. According to the party’s co-chairman Adakhan Madumarov, “we share the same values and hold one single position on all the critical issues. Our political party holds a strong view that Kyrgyzstan should go back to a pure presidential form of governance since the current semi-parliamentarian system has divided our country and led to anarchy, with politicians bearing no responsibility for their deeds.” The party’s other co-chairman Askar Salymbekov, an oligarch and owner of the country’s largest market Dordoi, added that his party received a number of proposals to unite with other political forces but found a strong compromise only with “Butun Kyrgyzstan.”

The union of these two relatively big political parties received varying reactions from local expert circles, with many predicting its success in the upcoming parliamentary elections in November 2015. During the last elections in 2010, Madumarov’s political party “Butun Kyrgyzstan” almost made it to the national parliament, lacking about 1 percent of the votes to overcome the required threshold. In 2011, Madumarov, a former journalist and a close ally of the ousted president Bakiev, former speaker of parliament and head of the country’s Security Council ran as a presidential candidate, receiving 15 percent of the votes and coming second in the race. Following the presidential elections, Madumarov remained an outspoken critic of the country’s political leadership until he was nominated as deputy Secretary General of the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States, a decision that was viewed by many as a sign of loyalty to Kyrgyzstan’s political leadership. Despite numerous claims that Madumarov would not participate in the upcoming parliamentary elections, he officially stepped from his position as deputy SG of the Turkic Council and returned to Kyrgyzstan in mid-May.

According to political commentators, the newly formed political union has a good chance of entering the national parliament. The former Bakiev ally Madumarov comes from southern Kyrgyzstan and continues to enjoy widespread support there. His party ally Salymbekov comes from the northern part of the country and his substantial financial wealth will allow for an impressive nationwide election campaign.

The newly formed political party constitutes a union between two political forces guided by short-term political interests. In the words of political analyst Mars Sariev, “the lack of program or ideological commonalities between them might endanger the party’s existence after the election period.” Other prominent members of the new party include Kyrgyzstan’s former Prime Minister Amangeldi Muraliev, former speaker of Parliament Altai Borubaev and a number of other formerly prominent state figures.

The tendency to merge political parties ahead of the parliamentary elections started a year ago. Last fall, the political parties Respublika and Ata-Jurt formed a new union, guided by similar regional and financial factors. According to MP Daniyar Terbishaliev, the political parties are at this stage preoccupied with forming their party lists. At a roundtable held in Bishkek, he stated that anyone willing to be in the so-called “golden ten” – the top 10 candidates on the party’s election list – must allocate from US$ 50,000 up to 1 million to the party fund, depending to their popularity among the electorate. Terbishaliev said this tremendous degree of corruption in the formation of party lists can only be regulated through tougher regulation of election funds and necessary adjustments to the law on elections.

In early May, Kyrgyzstan finally introduced new amendments to its election code. As predicted, the threshold for political parties to enter the parliament was increased from 7 to 9 percent, forcing political parties to merge. Also, according to the latest data from the Ministry of Justice, 200 registered political parties exist in Kyrgyzstan, a country with a population of 5 million.

Kyrgyzstan Debates Electoral System Reform

By Arslan Sabyrbekov (02/18/2015 issue of the CACI Analyst)

In October 2015, the second parliamentary elections under the 2010 Constitution are scheduled to take place in Kyrgyzstan. The country is in the midst of debating reform of its electoral system with political forces trying to define the “rules of the game” in their own interests. According to the recommendations of the Venice Commission, amendments to the electoral system must be introduced at least one year prior to the elections and Kyrgyzstan is already behind schedule.

The working group on reforming the existing electoral system, chaired by the head of the presidential administration Daniyar Narymbaev, recently issued a statement that all the amendments will be finalized and submitted to the parliament in February at the latest. The initiative on dividing the country into 9 constituencies was already adopted in the first reading. Other initiatives concern the formation of the voters’ list, the bill on conducting elections on the basis of biometric data, automation of the entire electoral process – from issuing ballots to counting the end election results as well as bills related to increasing the size of the parties’ required electoral fund and raising the electoral threshold to 10 percent from the current 5. These last two initiatives have led to widespread discussions in the country’s expert and political circles. According to the leader of the country’s ruling Social Democratic Party and one of the initiators of these norms, Chynybai Tursunbekov, “these initiatives will foster the country’s stability by getting rid of the smaller political forces and having 3 or 4 political parties in the parliament with a stable electorate and political capital.”

However, the country’s prominent civil society activists take a different position and perceive these initiatives as an effort to further consolidate power and another drawback in the country’s democratic development. “We should keep the threshold at 5 percent. Doubling the threshold will definitely remove the chance for smaller political parties to compete and the country risks ending up with one or two political parties in the parliament, like during the times of the first two ousted presidents,” noted Dinara Oshurakhunova, leader of the Bishkek-based “Coalition for Democracy and Civil Society.” Indeed, even the last parliamentary elections of 2010 with a threshold of 5 percent showed that this number is still high for Kyrgyzstan. Then, none of the political parties currently represented in the country’s legislature managed to pass the proposed 10 percent threshold, making the warning that the state machine could be used for the benefit of certain political forces in the upcoming elections quite legitimate. In 2010, only 5 parties out of 29 competing were able to enter parliament and represented less than 50 percent of the electorate.

According to local experts, this initiative has already led to the formation of unions between several major political parties: Ata Jurt and Respublika as well as Butun Kyrgyzstan and Bir Bol. According to political analyst Marat Kazakpaev, “these unions are not guided by ideological commonalities but rather by short-term opportunistic interests. This in turn damages Kyrgyzstan’s path towards developing a stronger parliamentarian system.” Kazakpaev has also noted that the initiative to increase the required election fund will make it impossible for smaller political parties to compete, forcing them to unite with others who have sufficient financial resources. Currently, only a few parties can manage to raise the required sum of 10 million KGS or around US$ 165,000.

In the meantime, the government is actively collecting biometric data on citizens, arguing that this will help holding the upcoming parliamentary elections in a fair and transparent manner. However, critics of the initiative see political interest behind it, claiming that citizens who have failed to submit their biometric data will be deprived of their right to vote, just like in the last presidential elections where hundreds of citizens were not included in the voters’ list and could not therefore cast their ballots.

In addition, electoral reform and especially its automation requires significant financial resources. Despite recent drawbacks in Kyrgyzstan’s democratic development, the European Union has expressed its readiness to allocate 10 million Euros for these purposes, along with Switzerland providing another US$ 2 million.

The author writes in his personal capacity. The views expressed are his own and do not represent the views of the organization for which he works.

Biometrics and Kyrgyzstan's 2015 Parliamentary Elections

By Zamira Sydykova (01/22/2015 issue of the CACI Analyst)

It is not even ten years since Kyrgyzstan went through two revolutions and an ethnic conflict of the summer of 2010, but we are now approaching new parliamentary elections which, as we are promised, will employ new IT technologies. However, even today, more than six months before the elections (they are planned for October-November 2015) these technologies are a subject of concern among the general population and of an even bigger unease among politicians.

This is the biometrics technology which the government of Kyrgyzstan is making hasty attempts to implement and is so readily reporting every day how many citizens and from which regions submitted their fingerprints.

For Kyrgyz people who already staged two revolutions, one of which (in 2005) was instigated specifically by the falsified elections, each suspicion sparks their revolutionary spirit. Cheated by previous governments, they are very wary of the biometrics and are very apprehensive because they believe that the new elections will spark new instability.

The biometrics technology was only tested during elections by a handful of countries – Mongolia, Bolivia and Venezuela. For instance, in Mongolia, a country with a population of 5 million people, the citizens were fingerprinted and the government retained the fingerprints. Polling stations were equipped with special machines that read the fingerprints of each voter, so on the day of the elections voters would just open up their computers and push on the candidate, party or law that they were voting for and that was it. Voters could vote from anywhere, even if they were in a different city or abroad. The votes were counted immediately.

However, neither Europe, nor the U.S. adopted this approach for reasons of security in general and specifically because this would constitute a violation of the citizens’ right to the secrecy of vote. Their discussions did not even include fingerprinting which in itself is a highly sensitive procedure involving storing highly sensitive information. For instance, in order to collect biometrical data of the 5 million people in Mongolia, 5,000 IT specialists were employed. It is unlikely that they were all sworn to secrecy.

Initially the government of Kyrgyzstan intended to implement an automated system, National Registry of Citizens, which would contain data for different categories of the population. It was later decided to combine this with the voter registration system so that they could obtain a list of voters and their identifying information – all in one registry. But when the campaign to collect biometric data commenced, a lot of issues surfaced. It is entirely possible that this issue would not have gained so much publicity were it not for the upcoming parliamentary elections.

Aside from purely technical issues which were in great detail presented in Kyrgyzstan by the civic organization Citizens’ Initiative for Internet Policy, and in particular, how biometric data will be stored in view of the peaked cyber-attacks around the world (e.g. during the elections in Estonia the database was kept in an embassy of a foreign state), there are many other problems which need to be solved.

Biometric voter registration is not prescribed by any law and neither is it part of the constitution which in Part 4 of Article 2 states, “Elections are free. Elections of the representatives to Zhogorku Kenesh, of the President and representatives of the local elective government bodies are held on the basis of universal, equal and direct right to vote by secret ballot”.

The Government of Kyrgyzstan has announced that those who did not submit their fingerprints would not be allowed to vote. Moreover, even if an individual did provide his or her biometric data but for some reason will be in any other place or outside of the country, the person will definitely not be able to vote. However, internal and external migration in Kyrgyzstan are very high. It is inevitable that civic activists will be filing complaints with the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of the Kyrgyz Republic about violation of their voting rights. This, in turn, will add to the chaos surrounding the upcoming political process in the country.

Part of the population is already of the opinion that the electronic voting will be easy to falsify, whereas the political elite who is poised to take part in the elections yet needs to figure out what rules will apply. At this time the parliament of Kyrgyzstan has on its docket four draft laws on elections. A serious concern is the impending increase of the 10 percent threshold and a non-refundable deposit (which will be just short of a million dollars). This will significantly impede the competitive abilities of political parties. Moreover, these restrictions are proposed by the governing pro-presidential coalition in the parliament. Rumors hold that the upcoming elections are being prepared by the presidential administration and the government and not by the Central Election Committee who now is not in charge of anything, not even of the voter registration.