The Organization of Turkic States' Push into Green Finance and Digital Innovation

By Lindsey Cliff

The Organization of Turkic States has expanded beyond its cultural foundations to address regional challenges through green finance, digital innovation, and artificial intelligence initiatives. Led by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the OTS established the Turkic Green Finance Council and proposed collaborative AI networks, responding to economic pressures from sanctions and oil price fluctuations. Key initiatives include the Turkic Green Vision promoting renewable energy development and the Green Middle Corridor for sustainable transport, alongside digitalization programs for customs procedures and cybersecurity cooperation. The establishment of institutional mechanisms—councils with rotating leadership, working groups of technical experts, and concrete investment vehicles—suggests organizational maturation. Whether these programs deliver tangible results will determine if the OTS evolves from primarily aspirational declarations into substantive economic and technological cooperation.

BACKGROUND:

The Organization of Turkic States has recognized the interconnected nature of climate, technology, and economy-related challenges. As such, the OTS has recently pushed, with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan leading the charge, for greater collaboration and integration in response to these threats. The fields of green energy, digital transformation, and smart innovation have become areas of pragmatic cooperation.

At the 2025 Gabala Summit, OTS leaders stressed "the importance of cooperation in the field of artificial intelligence and promote the integration of AI, green and digital technologies, and smart manufacturing systems into industrial strategies of the Member States, with a view to enhancing productivity, sustainability, and regional competitiveness through coordinated innovation and capacity-building efforts." This declaration marks a significant evolution for an organization that began with primarily cultural ambitions.

These initiatives respond to practical challenges facing landlocked Central Asian states. The growing global confrontation between the West and a loose anti-Western axis has added economic challenges for countries in the region. Mutual sanctions imposed by Russia and the West from 2014 onward hit the region hard, in combination with dramatic fluctuations in oil prices. Large-scale devaluations took place in the years following 2014, lowering purchasing power. While some entrepreneurs benefited from helping Russia circumvent sanctions, this hardly benefited the economy as a whole or reduced unemployment.

IMPLICATIONS:

In the domain of green finance and sustainability, the OTS has taken several concrete action steps. In Bishkek in November 2024, the Turkic Green Finance Council was established, with the Kazakh Astana International Finance Centre taking the lead. The Council will "provide OTS member states with an additional boost for developing green finance and attracting sustainable investments into regional projects."

The Council's inaugural meeting in September 2025 was attended by "heads and representatives of financial regulators, ministries of economy and finance, as well as stock exchanges from OTS Member States and Observers," supporting the possibility of tangible integration among all levels of the region's public and private sectors. Unlike summit-level photo opportunities, this meeting brought together the officials responsible for day-to-day implementation and strategy. The meeting resulted in the adoption of a joint communique expressing commitment to progress in sustainable development and environmental protection, "guided by the principles of Turkic Green Vision, as well as the Turkic World Vision 2040, and the OTS Strategy for 2022-2026."

The practical objectives of the Council, along with attendance by multiple levels of government and business leaders, suggest the OTS is moving from broad declarations toward institutional mechanisms for sustainable finance. The Turkic Green Vision proposes creation of several working groups: the Turkic Renewable Energy Alliance would promote renewable energy development; the Green Middle Corridor would create a sustainable transport route; the Turkic Biodiversity and Ecosystem initiative would promote collaboration in environmental protection and restoration; the Climate Change and Educational Awareness Program would promote study of climate issues and community disaster resilience.

Artificial intelligence and digitalization have also become main focuses of OTS integration. At the 2024 Bishkek Summit, Secretary General Kubanychbek Omuraliev highlighted collaborative projects across "e-commerce, technoparks, digital infrastructure development and cybersecurity" and suggested creation of a Turkic AI network and further investment in AI innovation and education. The organization also aims to streamline trade through digitized customs procedures, enabling more efficient transportation of goods.

Uzbekistan has been at the center of much of the AI and digitization agenda. Domestic investment in the digital sector has led to rapid modernization, increasing domestic internet access and speed, expanding IT service exports from $170 million to $1 billion, and attracting foreign investment. In AI, Uzbekistan has been investing within the framework of its "Strategy for the Development of AI Technologies through 2030." The goal is to "create a national AI model and train 1 million specialists." Already, the country has spent $50 million toward this goal, with 86 projects started and free online training programs launched. Through OTS AI Forums, the organization hopes to follow Uzbekistan's lead toward a more digital future with international investment in local IT and AI.

Kazakhstan is also attempting to lead in areas of AI and digital innovation, suggesting an intra-OTS Digital Monitoring Center. Kazakhstan's President Tokayev recently proposed dedicating an upcoming informal OTS summit to the theme of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Development, and he made digitalization and AI the centerpiece of Kazakhstan's national strategy in a September 2025 public address. The aim is to set up Kazakhstan as a "fully digital country" within three years, establishing a dedicated ministry for digitalization and AI, developing legal codes for AI governance, and developing digital currencies.

In these areas, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are taking leading roles. Kazakhstan not only hosted the inaugural Green Finance Council but also suggested its creation. Of course, Uzbekistan now leads the region in AI readiness and is making significant domestic progress on its digitization and AI agendas. Future OTS summits will likely maintain continued focus on AI, digital innovation, and sustainable development.

CONCLUSIONS:

The Kazakh-proposed Digital Monitoring Center represents potential cybersecurity and defensive integration—a real avenue for pragmatic cooperation. The transnational nature of climate threats and the internet necessitate a collective regional response. While the Turkic Green Vision adds language about supporting "cultural and natural values of the region," and third-party observers recognize IT as a way to "preserve cultural heritage," the primary drivers are practical: economic development, energy security, and regional competitiveness.

These initiatives respond to genuine needs. The rapid development of initiatives in finance, digitalization, and green energy demonstrates that the OTS is expanding beyond its cultural foundations. However, questions remain about implementation. As with many OTS initiatives, movement from declarations to concrete results will determine whether these programs represent genuine integration or remain primarily aspirational.

The establishment of institutional mechanisms—councils with rotating leadership, working groups of technical experts, and concrete investment vehicles like the Turkic Investment Fund—suggests a maturing organization. If these initiatives deliver tangible results in coming years, they will mark the OTS's evolution from a primarily cultural organization into a platform for substantive economic and technological cooperation.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Lindsey Cliff is a junior fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council, who is also pursuing a Master’s degree at Georgetown University in Eurasian, Russian, and East European Studies.

From Rivalry to Recognition: The OTS's Evolving Approach to Tajikistan

By Lindsey Cliff

The Organization of Turkic States has evolved its approach toward Tajikistan, shifting from explicit support for Kyrgyzstan during border conflicts to more inclusive language. Early OTS statements emphasized brotherly solidarity with Kyrgyzstan while implicitly attributing blame to Tajikistan, prompting sharp criticism from Dushanbe. Following diplomatic progress culminating in the March 2025 Kyrgyz-Tajik border treaty, OTS rhetoric shifted significantly. The organization’s March 2025 statement on the trilateral Khujand summit explicitly included Tajikistan among three brotherly nations, marking the first time such fraternal language extended to a non-Turkic state. This evolution reflects practical necessity—avoiding alienation of a major regional state—and organizational maturation as the OTS launches its plus framework for engaging non-member states.

BACKGROUND:

Tajikistan has been the topic of six official OTS statements since 2021—all in the context of the Tajik-Kyrgyz border conflict. Through these statements runs a common thread: member solidarity among Turkic states. Yet the rhetoric has evolved significantly, tracking changes in the situation on the ground and reflecting the OTS's maturation as a regional organization.

Understanding this evolution reveals how the OTS is navigating the tension between its ethnolinguistic foundation and the practical requirements of regional cooperation. The trajectory of OTS statements on Tajikistan offers insight into whether the organization can transcend ethnic boundaries to become an inclusive platform for regional stability.

The early statements from 2021-2022 established clear patterns. The April 2021 statement, issued during border clashes, referred to "brotherly Kyrgyzstan, the founding member of the Turkic Council," explicitly emphasizing ethnic and cultural kinship while omitting similar recognition of Tajikistan. The statement appealed to shared Islamic and cultural identity as the moral basis for peace: "In the holy month of Ramadan, we need to do our utmost to further unite and put aside our differences." This extended an intra-Turkic appeal rather than adopting a neutral, diplomatic tone.

The statement emphasized "the contribution of the Kyrgyz side to the re-establishment of peace," without mentioning Tajikistan's efforts, implying the ongoing conflict was the fault of Tajikistan's failure to commit to peace. The closing line committed the Secretariat to remain "in close contact with the Government of brotherly Kyrgyzstan," signaling preferential solidarity with the Turkic side of the conflict.

The January 2022 statement followed similar patterns. Again, the OTS expressed "support to the efforts of the Kyrgyz Republic to find a peaceful solution" while calling for dialogue "based on mutual understanding, mutual respect, good neighborliness and coexistence." The contrast was striking: "good neighborliness and coexistence" for Tajikistan versus "brotherly" solidarity for Kyrgyzstan. The September 2022 statement went further, explicitly condemning "the aggression with the use of heavy military weapons against civilians and civilian infrastructure" while expressing support for "the efforts of the Kyrgyz Republic, founding member of the OTS, for a peaceful solution."

IMPLICATIONS:

The Tajik government clearly noticed this pattern. Following the September 2022 statement, Tajikistan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned the OTS Secretary General's statement as "hindering the efforts of the Tajik and Kyrgyz sides to resolve all bilateral issues exclusively by political and diplomatic means." The Ministry called the OTS statement "deeply regrettable, as it is at odds with the goals declared by the Organization, one of which is to make a joint contribution to ensuring peace and stability throughout the world."

This response illustrates the practical impact of one-sided statements. The Tajiks claimed the OTS impeded progress on peaceful diplomatic solutions through its skewed narrative. For an organization aspiring to regional significance, alienating a key Central Asian state posed obvious problems. Tajikistan shares borders with Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and China, making its exclusion from regional cooperation mechanisms a significant limitation.

The turning point came with actual progress in the border dispute. On March 13, 2025, the Presidents of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan signed a Treaty on the State Border in Bishkek. The OTS issued two statements on this development that marked a subtle but significant shift in rhetoric. The statements welcomed the agreement warmly and noted it was "achieved through diplomacy and dialogue." While these statements still didn't explicitly call Tajikistan "brotherly," they avoided the one-sided emphasis of earlier statements.

More significant was the March 31, 2025 statement on the trilateral summit of Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan in Khujand. For the first time, the OTS Secretary General referred to "three brotherly nations," explicitly including Tajikistan in the fraternal vocabulary previously reserved for Turkic states. The statement called the summit "epochal" and praised "the unwavering efforts of the three brotherly nations in deepening regional partnership."

This represented a genuine shift—but one that maintained certain boundaries. The concluding sentence pledged support for "unity and cooperation among Turkic and neighboring states," still categorizing Tajikistan as neighboring rather than fully integrated. Tajikistan was offered a relationship within the already-defined Turkic community rather than recognition as its own self-defined actor. Nevertheless, the shift from implicit antagonist to "brotherly nation" marked significant evolution.

CONCLUSIONS:

What explains this shift? The most obvious factor is the changed situation on the ground. As long as armed clashes continued along the Kyrgyz-Tajik border, the OTS faced pressure to support its member state. Once diplomatic progress produced actual agreements, the organization could adopt more inclusive language without appearing to abandon Kyrgyzstan.

The OTS's broader ambitions also likely influenced this evolution. At the 2025 Gabala Summit, the organization launched the "OTS plus" framework to structure relationships with non-Turkic states. Maintaining openly hostile rhetoric toward Tajikistan while proposing inclusive mechanisms would appear contradictory. The trilogy of summits—Kyrgyz-Tajik bilateral agreement, Kyrgyz-Uzbek-Tajik trilateral summit, and the OTS Gabala summit—created momentum toward regional cooperation that required softer rhetoric.

Uzbekistan's role may have been particularly important. As the OTS member bordered by Tajikistan and the country hosting the trilateral summit, Uzbekistan had clear interests in promoting inclusive regional cooperation. Uzbekistan's enthusiastic embrace of OTS membership from 2019 onward coincided with President Mirziyoyev's broader policy of improving relations with all neighbors. Uzbekistan likely advocated internally for more inclusive OTS approaches to Tajikistan.

The evolution of OTS rhetoric on Tajikistan thus reflects both practical necessity and organizational maturation. An organization aspiring to regional significance cannot indefinitely alienate major regional states. The shift from implicit antagonism to tentative inclusion suggests the OTS recognizes this reality. Whether "OTS plus" will genuinely integrate non-Turkic states as equal partners, or merely formalize their status as perpetual outsiders, remains to be seen. But the trajectory of OTS statements on Tajikistan—from pointed solidarity with Kyrgyzstan to inclusive "brotherly" language—indicates the organization is navigating tensions between its ethnic foundation and regional cooperation requirements.

For policymakers both within and outside the region, this evolution merits attention. It suggests the OTS may prove more flexible and pragmatic than its ethnolinguistic foundation initially implied. How the organization manages the tension between Turkic identity and inclusive regionalism will significantly impact its effectiveness as a platform for addressing shared challenges in security, transportation, and economic development.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Lindsey Cliff is a junior fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council, who is also pursuing a Master’s degree at Georgetown University in Eurasian, Russian, and East European Studies.

The Rise of Security and Military Cooperation among Turkic States

By Svante E. Cornell

In October 2025, the Organization of Turkic States (OTS) convened a pivotal summit in Gabala, Azerbaijan, demonstrating its emergence as a significant geopolitical entity in the Eurasian landscape. During the summit, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev emphasized the OTS's evolution into a key geopolitical center, while Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev referred to it as an authoritative structure uniting Turkic populations. This marked a critical juncture in the organization’s development, solidifying its influence in a region that links the Mediterranean to Central Asia.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

BACKGROUND: The level of interest in Turkic cooperation has diverged over time and among the Turkic states. Some, like Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, have consistently been enthusiastic participants. Türkiye, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, on the other hand, have seen fluctuations in their enthusiasm. It is mainly in the last 7 to 8 years that a consensus has developed on the importance of Turkic cooperation.

Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev in the late 2000s proposed the creation of a Council of Turkic-speaking States, which was formed in 2009. Twelve years later, it was turned into a formal inter-state organization, the Organization of Turkic States (OTS).

Up until recently, the intensification of cooperation among Turkic states was focused on non-security areas. Still, the OTS provided a platform where individual member states developed dialogue on security issues in both bilateral and trilateral formats. Thus, in parallel with the intensification of OTS activities, there has been a parallel rise in security, intelligence, and defense agreements among members of the organization.

Two types of formats can be seen in the growing security cooperation within the Turkic world. A first, not surprisingly, involves Türkiye’s bilateral security ties with other Turkic states. Importantly, however, a second format involves cooperation among those other states themselves, without Turkish participation.

The first type of format involves the growing Turkish engagement with Azerbaijan and the Turkic states of Central Asia. A key step was the formation of a defense treaty between Türkiye and Azerbaijan in the shape of the Shusha Declaration of June 2021, the same year OTS was created. The Shusha Declaration followed on the decisive role of Türkiye in supporting Azerbaijan in the 2020 Second Karabakh War. That, in turn, followed upon Türkiye’s active involvement in conflicts in Syria and Libya, where Ankara actively sided against Moscow-supported proxy forces; had a decisive impact on the outcome of the conflict; and managed to do so while maintaining a functional, if transactional, relationship with Moscow. There is no question that this was duly noted in Central Asian capitals and made a security and defense relationship with Türkiye increasingly attractive for the Turkic states of Central Asia.

In fact, Türkiye stands out among external powers in the region as it has shown a willingness and ability to engage across the spheres of security, intelligence, and defense (where Europe and the U.S. have generally been absent, with the notable exception of NATO’s Partnership for Peace program). As Richard Outzen put it, all Turkic states of Central Asia are at one point or another in the process of developing “military education exchanges, training and exercises, a broader range of equipment and defense technologies, and, perhaps most importantly, development of common doctrine and operational approaches” with Türkiye.

While Azerbaijan has reached the level of near-complete integration with Türkiye, other states are at less advanced stages of the process. They may not desire the same level of military integration with Türkiye as Azerbaijan does, but all are intensifying exchanges with Ankara. Kazakhstan began to expand military ties with Türkiye in 2020 when it signed an agreement for joint defense and industrial projects. That was followed by a protocol for intelligence cooperation in 2022, as well as an enhanced strategic partnership. Kazakhstan purchased Turkish UAVs and now holds a license to produce them in Kazakhstan.

Uzbekistan also started its process of deepening military ties with Türkiye. In 2022, the two countries signed a defense cooperation agreement on intelligence cooperation, as well as training and logistics. In November of that year, a further agreement included military education and defense industrial cooperation. As for Kyrgyzstan, it has purchased several types of Turkish UAVs, including TB-2 Bayraktar drones. Turkmenistan has also purchased Bayraktar drones. In late December 2023, Turkmenistan’s top leadership welcomed leaders of Türkiye’s largest defense industrial companies and publicly spoke of the potential role of these firms – and Türkiye – in helping Turkmenistan strengthen its defense capabilities.

As noted, not all security and defense cooperation involves Türkiye. On a bilateral level, security and defense cooperation has grown rapidly involving Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, and most recently Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan. These three states have all raised their respective sets of bilateral relations to the level of allied relations, including through the formation of “Supreme Interstate Councils” for inter-state coordination on a government level. In the defense sphere, cooperation has developed through military exchanges, joint exercises, intelligence sharing, and the development of the defense industry.

Until recently, it was obvious that the development of Turkic Cooperation under the Organization of Turkic States served as a catalyst for the myriad of bilateral agreements in the security and military field. Yet formally, while OTS member states have discussed holding security consultations and developing a common stance on security issues ever since the Turkic Council’s Almaty Summit in 2011, defense and security cooperation remained outside the purview of the OTS. This has nevertheless begun to change as the OTS has more recently taken steps to expand into the security field.

IMPLICATIONS: The OTS’s organizational move into the field of security and defense dates to the summit in Samarkand in 2022. The member states “went beyond consultations by adding a new dimension to their security cooperation ... they called for closer cooperation and military collaboration in the defense industry.”

Similarly, at the following summit in Astana in November 2023, the final communiqué called for “closer cooperation in the field of defense industry and military collaboration.” At the summit, a key advocate for the intensification of military cooperation was Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, who stressed during his speech that “the main guarantor of security becomes defense potential” in the developing security situation and that he “believe[s] that cooperation between the member states in areas such as security, defense, and the defense industry should be further increased.” Following his re-election in 2024, Aliyev subsequently declared that the OTS was the main vector in Azerbaijani foreign policy.

The eleventh summit in Kyrgyzstan in 2024 focused on the adoption of a “Charter for the Turkic World” which did not specifically go into matters relating to security and defense. Still, a seed was planted: the charter includes language that “the Turkic people will strive together to prevent any actions and threats aimed at undermining their unity, solidarity, and dignity.” While far from a mutual defense clause, it is reminiscent of how the EU adopted a solidarity clause before moving to the mutual defense clause adopted with the EU’s Lisbon treaty. At this summit as well, Aliyev repeated his earlier call, saying, “Given the growing global threats, our cooperation in defense, security, and the defense industry is of tremendous importance.”

In July 2025, the first meeting of the heads of defense industries of the Turkic states was held in Istanbul, under the banner of the OTS. The meeting mainly served to take stock of existing bilateral cooperation programs and to plan for multilateral cooperation in the future. Azerbaijan has offered to host a second meeting in 2026.

The 2025 OTS Summit in Gabala, Azerbaijan, proved a turning point. The theme for the summit was “Regional Peace and Security,” indicating the organization’s more open embrace of security issues. The leading section of the summit’s declaration focused on security issues and particularly put forward the objective of signing a “Treaty on Strategic Partnership, Eternal Friendship, and Brotherhood of Turkic States.” While not included in the formal communiqué of the summit, Azerbaijan offered to host the first military exercises under the banner of the OTS.

CONCLUSION: It is clear that, in the past few years, the OTS has been rapidly expanding its purview into the security area, defense industrial cooperation, and military coordination. It remains to be seen whether the OTS will transform into a formal alliance, as seems to be the intent of at least several of the member states. What is clear is that the OTS has turned into a vehicle for regional middle powers – specifically Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan – to work to fill the security vacuum that has plagued the heart of Eurasia over the past three decades. That vacuum has been the result of the weakness of internal security arrangements in the region, as well as the prevalence of security arrangements dominated by external actors, such as Russia’s CSTO. While Türkiye is prominent among the OTS member states due to its military capabilities and the size of its economy, it is clear that the Turkic “middle powers” have been at least as forceful as Türkiye in driving the rise of Turkic cooperation.

Turkic cooperation is expanding and intensifying so rapidly that it can no longer be ignored. In many ways, the expansion of Turkic cooperation is directly in line with American and European policy objectives in Central Asia and the Caucasus. OTS activities are largely complementary to Western policies, while also filling voids that Western powers themselves have proven unwilling or unable to fill. For both the EU and the United States, the role of the OTS in maintaining a balanced international environment in Greater Central Asia has become significant enough that the factors limiting Western engagement with the OTS should not obscure the clear alignment of interests that is at play.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Svante E. Cornell is Research Director of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.

Turkey and the Organization of Turkic States: A Quest for Pan-Turkism?

Halil Karaveli

April 11, 2024

The Organization of Turkic States (OTS) represents an institutionalized restoration of a pre-Soviet pattern of Turkic cooperation. A common linguistic, as well as the more dubitative no-tion of a cultural heritage that is supposed to unite the lands between Istanbul and Samar-kand contribute to furthering a sense of belonging among the member states of the OTS. Yet Turkic unity is valued and promoted only as far as it aligns with the economic-political state interests of the individual members of the OTS, and is discarded when it contravenes those in-terests. The deepening of Turkic cooperation answers to the material interests of the partici-pating states. The Turkic states’ reluctance to recognize and include the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus underlines the ultimately non-ethnic character of their cooperation, and is also indicative of Turkey’s limited ability to exercise an uncontested leadership role among the group of Turkic states.

Security and Military Cooperation Among the Turkic States in the 2020s

Richard Outzen

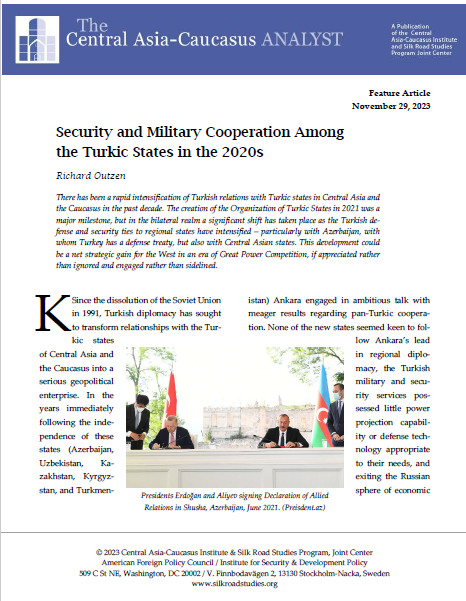

December 8, 2023

There has been a rapid intensification of Turkish relations with Turkic states in Central Asia and the Caucasus in the past decade. The creation of the Organization of Turkic States in 2021 was a major milestone, but in the bilateral realm a significant shift has taken place as the Turkish defense and security ties to regional states have intensified – particularly with Azerbaijan, with whom Turkey has a defense treaty, but also with Central Asian states. This development could be a net strategic gain for the West in an era of Great Power Competition, if appreciated rather than ignored and engaged rather than sidelined.