Institutionalizing Central Asian Regional Cooperation

By Svante E. Cornell

In early August, Central Asian presidents met in Awaza in Turkmenistan along the sidelines of a UN conference, in preparation for their seventh formal consultative meeting, which will take place later this fall. The process of institutionalizing regional cooperation is progressing apace, as Central Asian cooperation has expanded from informal summits of presidents to a more formalized structure that is also branching out into meetings at the ministerial level and between representatives of parliaments. For the process to bear fruit, however, the Central Asian presidents will need to take more concrete steps to set up formal regional structures of cooperation.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

BACKGROUND: When Central Asian Presidents met in Awaza, Turkmenistan, on August 5 for a forum to prepare their more formal upcoming consultative meeting, it was difficult not to take a step back to note how different the situation is from only a decade ago. To begin with, until 2017, Central Asian leaders had met frequently in mechanisms involving other powers but rarely on their own. For years, they had built dialogue mechanisms with outside powers, Japan being the first to inaugurate a regional dialogue in 2004. The EU, the United States, and many others followed suit. But for close to a decade, Central Asian leaders did not have a regular format in which they met only as Central Asians, without foreign powers involved. Of course, this did not mean they had not met jointly for specific purposes, most notably the Treaty creating a Nuclear Free Zone for Central Asia, signed in Semey, Kazakhstan, in 2006.

Furthermore, the location of the meeting in Turkmenistan speaks volumes. During previous iterations of Central Asian efforts to build regional cooperation, Turkmenistan typically remained aloof, citing its permanent neutrality. The fact that Turkmenistan is now an avid participant in these efforts is truly a major development.

The rebirth of Central Asian regional cooperation got kick-started in 2017, when Kazakhstan’s then-President Nursultan Nazarbayev, responding to a suggestion by Uzbekistan’s new President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, convened a meeting of Central Asian Presidents. When this consultative meeting took place in 2018, it was the first time in almost a decade that Central Asian presidents had met without outsiders present. Since then, meetings between the presidents have taken place on a yearly basis.

The emphasis on presidential meetings is a reflection of the political realities of Central Asia. With political systems that are largely organized top-down, it is only natural that regional cooperation will be structured in a top-down manner, in the form of consultative meetings of the presidents. But for regional cooperation to be successful, it cannot only or even primarily be focused on presidential meetings. Quite to the contrary, regional cooperation will be successful when government agencies, trade councils, and civil society groups across the region cooperate in a structured manner with each other, through formal mechanisms or institutions.

Such a vision was launched at the fourth meeting of Presidents in Cholpon-Ata in 2022, where presidents approved a broad range of initiatives covering mutual relations in more than two dozen spheres, ranging from law, trade, sports, investment, visas, and education to security. Similarly, the 2024 sixth consultative meeting led to the adoption of a roadmap for the development of regional cooperation for 2025-2027 and an action plan for industrial cooperation among Central Asian states for the same time period.

IMPLICATIONS: More steps have been taken toward the building of institutions. Most importantly, the Presidents resolved at the 2023 Dushanbe Summit to establish a Council of National Coordinators of the presidential consultative meetings. Designed to “enhance the day-to-day effectiveness of interstate engagement and provide coherence to ongoing initiatives,” this body might in fact form the embryo of institutionalized Central Asian regional cooperation.

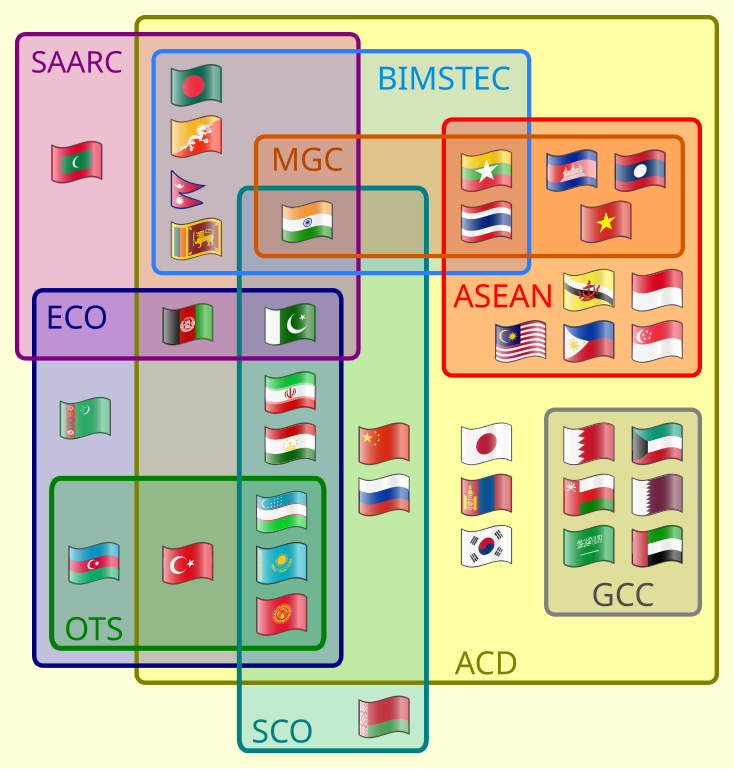

Further moves came at the 2024 summit in Astana, where the five presidents approved a strategic vision proposed by Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev entitled “Central Asia 2040”, subtitled a "Concept for the Development of Regional Cooperation." This strategic vision builds on President Tokayev’s concept of “Central Asian Renaissance,” outlined in a policy article published ahead of the 2024 summit. In this article, the Kazakh leader outlined a vision of a more integrated region that also serves as an interlocutor on the world stage with great powers and international organizations. As he points out, this is already beginning to take place as a result of deeper Central Asian coordination in multilateral bodies like the United Nations, as well as in organizations like the SCO in which Central Asian states are represented.

The “Central Asia 2040” document spelled out a vision to deepen integration in concrete areas like trade, energy, transport, environment, digital connectivity, but also specifically included the task of strengthening a joint Central Asian cultural identity. Beyond that, it mentions for the first time the institutionalization of meetings of heads of state into a formal regional structure. Accepting that the consultative meetings of Heads of State constitute “the cornerstone of political coordination,” it declares that this format is being institutionalized as a “permanent regional structure” and declares that it is being broadened beyond the Heads of State. It explicitly expands the formats of cooperation to include “parliaments, ministries, civil society, businesses, and think tanks.” It should be noted that minister-level dialogues are already underway: ahead of the 2024 consultative summit, there was a meeting of Central Asian transport ministers, as well as a meeting of energy ministers.

The five states have already initiated a movement to develop parliamentary cooperation. A first Central Asia Inter-Parliamentary Forum was held in Turkestan, Kazakhstan, in February 2023, and was followed by a second convocation in Khiva, Uzbekistan, in September 2024. Key matters discussed included cooperation on oversight over high-level agreements and the harmonization of legislation across Central Asia, as well as the development of a legal framework for a common economic space and for fostering cooperation in industry and transport.

In addition to these formal steps, informal contacts among government officials across Central Asia have increased exponentially over the past decade. Far from being isolated from each other as in the past or interacting only through formal means, representatives of Central Asian government agencies are now comparing notes and learning from each other in ways that were not imaginable a decade ago.

The development of Central Asia-wide regional institutions is thus a work in process, but that process will likely take time. To some degree, major decisions taken at the yearly consultative meetings continue to be determined by the lowest common denominator. It is well known that there are diverging levels of enthusiasm for how deep regional cooperation should be, a question that has been marring Central Asian regionalism from the start.

Turkmenistan and Tajikistan were long perceived as more skeptical to institutionalizing regional cooperation. But Turkmenistan’s hosting of the forum in Awaza shows its full participation in the process. And the recent progress in Kyrgyz-Tajik relations has also changed Dushanbe’s approach. When Kazakhstan’s suggestion for a friendship treaty among Central Asian states was raised at the 2022 Cholpon-Ata summit, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan refrained from signing. Tajikistan’s reticence could be attributed to its border conflict with Kyrgyzstan, which has since been resolved. Following the landmark Khujand Treaty of April 2025 that marked the resolution of the remaining border issues between the two countries, as well as Uzbekistan, Tajikistan’s President in late August signed the friendship treaty during a visit by Kazakhstan’s foreign minister Murat Nurtleu. It remains to be seen whether Turkmenistan will now also follow suit.

CONCLUSIONS: For Central Asian regional cooperation to be successful, it cannot long avoid speeding up the process of institutionalization. There is a limit to the momentum that can be achieved by pronouncements at the presidential level, even if those are followed up by ad hoc meetings at the ministerial level or between parliamentary representatives. Already, the implementation of the agreements reached at Consultative Summits is unclear. As the “low-hanging” fruit of easily achieved steps is picked off, achieving tangible results without regional structures will be increasingly difficult. For regional cooperation to be felt at the societal level and to become irreversible, structures of cooperation will be needed. That can ensure that presidential pronouncements are actually implemented at the national level. Furthermore, such regional structures can themselves identify and prioritize the main issues facing deeper regional cooperation in Central Asia.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Svante E. Cornell is Research Director of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.